When a Joke Is Not Just a Joke

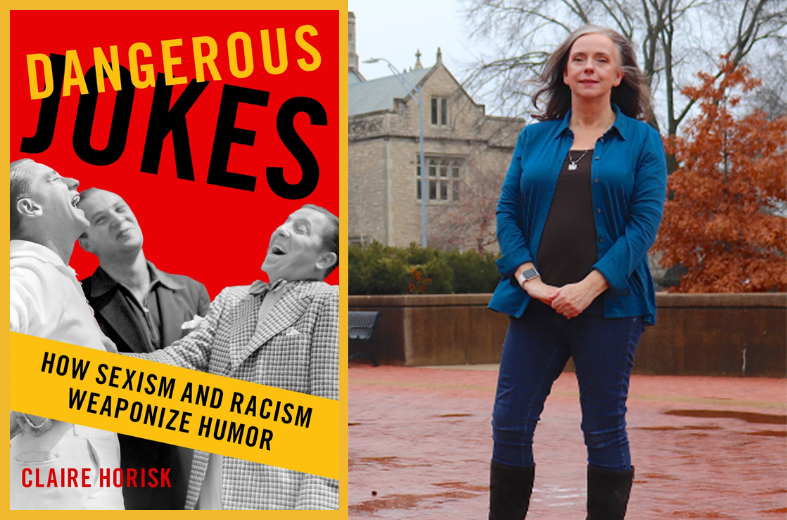

MU Philosophy Researcher Explores How Racism, Sexism Weaponize Humor

Claire Horisk’s latest research project — and her first book — began with a question: Can people hide behind the masquerade of “it’s just a joke” when telling racist, sexist or demeaning jokes?

The answer is “No,” but following a conversation on the subject, Horisk, an associate professor of philosophy at MU’s College of Arts and Science, explored the existing research to learn more about the why.

“You know how academics are; like Hermione Granger in the ‘Harry Potter’ novels, we tend to think that reading something is a good first step in tackling a problem,” she said. “But I couldn’t find an article that gave a satisfying answer to the question, so I started writing one myself.”

The result is “Dangerous Jokes: How Racism and Sexism Weaponize Humor,” published by the esteemed Oxford University Press on Feb. 27.

“It became clear that to explain why people shouldn’t tell some jokes … I needed to write a book, not just a journal article,” said Horisk, whose research interests investigate the philosophy of language, including how language shapes society. “Furthermore, I couldn’t do a good job without reading widely in other disciplines. I started with court cases about hostile environment harassment and with work in social psychology, and gradually my plan for the book came together.”

“Dangerous Jokes” focuses on interpersonal humor and not professional comedy found on TV or in comedy clubs. The work offers an accessible read for general audiences for how prejudice spreads while meeting the scholarly needs of students and scholars who work on philosophy, linguistics, race, gender and social psychology, Horisk said.

“My book draws on and develops contemporary pragmatics — the study of how people communicate more than literal meaning in conversation — to explain how demeaning jokes and jocular remarks convey demeaning ideas, and it sheds new light on the moral significance of conversation by explaining how telling demeaning jokes and listening to them are morally evaluable actions,” she said. “The book fills a gap in the growing literature in the philosophy of language on demeaning and antagonistic speech.”

What is your response to “Dangerous Jokes” being published?

Mostly, I’m excited. Working on the book, I had many interesting conversations with people about their experience with demeaning humor. People would get engaged when I explained the project — even if they had asked about my research only out of politeness — and I’m glad that the book will open up a conversation about the harms of humor. I earned my undergraduate degree in philosophy and psychology at the University of Oxford, and consequently publishing with Oxford University Press is especially meaningful.

What first drew you to research the philosophy of language?

I was one of those kids who would read the dictionary — as well as lots of fiction, including my fair share of trashy novels — and I have always been interested in language. I took a course in philosophy of language in my first semester of graduate school, and I was hooked. I particularly loved the unit about how people can communicate more than they say. Although I worked on other issues for the first part of my career, “Dangerous Jokes” has brought me back to that early passion: I argue in the book that jokes are a wily way of communicating negative stereotypes and ideas about social groups.

What are some key points you hope readers take away from the book?

The most important takeaway is that contrary to popular wisdom, humor causes harm. In fact, jokes are more effective in conveying stereotypes than stating the stereotype openly. It’s also a mistake to think that it’s fine to tell derogatory jokes about your own group. In fact, if a Muslim person tells jokes about Muslims, it is more likely to cause harm than if a Christian tells the same joke. Furthermore, I argue that it's not just joke-tellers who are at fault; listeners can be at fault as well. Finally, the culture and the position of the target group in the social hierarchy matter to the morality of joking. For example, telling derogatory jokes about CEOs or billionaires is different, from a moral point of view, than telling derogatory jokes about women or African Americans.

You talk about ways people can challenge belittling speech. What are some tips for readers based on your book and research?

There’s also a postscript where I give some practical, evidence-based tips. It’s important to know that challenging belittling speech is often effective, so it’s not a waste of energy, but it’s more effective if the challenger isn’t the target. For example, if a woman challenges sexist speech, they may be unfairly dismissed as whiny or over-sensitive, but a challenge from a man might work. Challenging by appealing to the culprit’s sense of fairness can work well. However, prefacing the challenge with things like, “I know you’re not racist, but …” tends to make challenges less effective.

How did the University of Missouri support you in creating this book?

Mizzou has helped in many ways. The Research Council, the College of Arts and Science and the Provost Great Books Program provided research leave or course releases that gave me valuable time at pivotal points in the project. The writing retreats that are hosted by the Campus Writing Program are productive for me, especially when I am drafting new material. The Mid-Career Research Development Fellows Program has also provided structure and advice as I worked my way through the final phases of the book. If it weren’t for these sources of support, the book would have taken much, much longer.

Your husband is Rex Cocroft (professor of biological sciences). Do your two different areas of research feed off each other or maybe help form your approach to your research?

Rex and I both work on communication — him on insect communication and me on human communication. We have written a co-authored paper, which honestly was much easier on our relationship than assembling a piece of IKEA furniture. However, Rex’s greatest impact on my work is his extensive knowledge about animal communication more broadly. Historically, many philosophers have thought human beings — including their capacity for language — must be markedly different from animals in some way, and so they haven’t thought much about how knowledge of animal communication can help us understand human communication. While the way humans communicate isn’t exactly the same as the way any animal communicates, hanging out with Rex has led me to think more about commonalities with our animal cousins and our shared evolutionary history.

Do you have a favorite clean joke you are willing to share?

Hmmm, that’s a tricky one. My sense of humor is spontaneous; I love puns, for example, and hardly ever tell jokes. But here’s one I like: A panda walks into a café. He orders a sandwich, eats it, then draws a gun and fires two shots into the air. “Why?” asks the confused waiter, as the panda makes towards the exit. The panda produces a badly punctuated wildlife manual and tosses it over his shoulder. “I’m a panda,” he says at the door. “Look it up.” The waiter turns to the relevant entry, and sure enough, finds an explanation. “Panda. Large black-and-white bear-like mammal, native to China. Eats, shoots and leaves.” (Truss 2006)

ORDER THE BOOK

“Dangerous Jokes” is available now for pre-order and will ship at the end of February. Use code AAFLYG6 for a 30% discount directly from Oxford University Press. “Dangerous Jokes” also will be available through major online booksellers, including as an e-book.

This article was originally published on the Research, Innovation & Impact site.